Free self-guided walking tour through Florence’s golden age 1400 – 1500

Introduction Florence City Walk

Florence seems to have been specially designed to wander around aimlessly while marvelling at an overwhelming collection of works of art and architectural masterpieces. You don’t need a car, bicycle or Vespa. The city centre is compact enough to explore on foot and spacious enough to spend a few days in it without ever feeling like you’ve seen it all.

This is not a classic walking tour where you can quickly tick off the most important highlights. Here no visit to the Uffizi museum, the Galleria dell’ Accademia or the Ponte Vecchio – sights you would probably visit anyway.

What you do get in this walk is a mix of world-famous and lesser-known sights, interspersed with stories that want to give you an idea of life in Florence in its golden 15th century and make you think about how Florence was able to produce so many geniuses in those hundred years – a question that is examined in depth in the book The City of Genius.

The city walk through Florence is about eight kilometres long. If you go out early in the morning, walk briskly and only focus on the walk, you will be finished in two hours. But I assume this is not your intention. Take your time and make it a day trip with a few stops for a quick espresso, a slow ribollita or, for the daredevils, a lampredotto sandwich with a strong Chianti wine.

This city walk is inspired by the book The City of Genius (De geniale stad) by Koen De Vos.

Route Florence City Walk

Are you reading and watching this walk with your tablet or smartphone and do you have access to the Internet? Click on the maps below and you will be redirected to Google Maps.

View Florence City Walk in Google Maps.

Overview sights

- Gates of Paradise

- Dome of Florence Cathedral

- Ospedale degli innocenti – Foundling hospital

- Donatello, David (in Bargello)

- Palazzo Vecchio (or Palazzo della Signoria)

- Illustrious Florentines

- Santa Croce

- The dyers’ district

- Corridoio Vasariano

- Palazzo Davanzati

- Medici-Riccardi Palace – Cappella dei Magi

- San Lorenzo

- Santa Maria Novella

- Ognissanti

- Ponte Amerigo Vespucci

- Brancacci Chapel (Santa Maria del Carmine)

1. Gates of Paradise

Piazza di San Giovanni

Start at Piazza di San Giovanni, between the main entrance of the cathedral and the baptistery.

View position in Google Maps.

Nowhere better to start your walk in Florence than at the Porta del Paradiso (Gates of Paradise), the life’s work of Lorenzo Ghiberti (1381–1455). The Porta del Paradiso is one of the three portals of the Battistero (Baptistery) di San Giovanni, the shining golden gates opposite the entrance to Florence Cathedral.

In 1336, more than a century after the baptistery was completed, Andrea Pisano had decorated the south portal, the first of the three portals. Sixty-five years later, at the beginning of Florence’s golden age in 1401, the Florentines finally thought it was time to decorate the other two portals. To select the most suitable artist, the Arte di Calimala (guild of cloth merchants) organized an art competition, a device the Florentines often resorted to for assigning an artistic commission and to scout out new talent. The odd thing is that they did so at a time when Gian Galeazzo Visconti, the Count of Milan, was at the gates of Florence, the Florentine economy had come to a standstill due to the war and the plague was still lurking around the corner. Not the most appropriate time to organise large and expensive festivities, one would think, but the Florentines couldn’t care less.

The briefing for this art competition was drawn up by a jury that included Giovanni di Bicci de’ Medici, the founder of the emerging Medici Bank. The first task of the jury was to select the most appropriate candidates from the list of applicants. The seven (some say six) lucky ones were given the assignment to create a bronze relief with the sacrifice of Izaak as the subject. They had to finish it within the year.

Of those seven (or six) bronze reliefs, two designs stood out. Not those of the older established names, but those of two newcomers, Lorenzo Ghiberti and Filippo Brunelleschi. Brunelleschi was twenty-four years old at the time of the competition and did not have any masterpieces to his name. Ghiberti was one year younger and had not even been officially registered as a goldsmith yet. After a long period of hesitation, the jury took the decision. Ghiberti’s design won the competition but both gentlemen were invited to work on it together. To everyone’s surprise, Brunelleschi, who was not well known at the time, refused the commission. He did not like working together with other people and certainly not on another artist’s design.

Ghiberti worked about fifty years on the two gates, first the north portal and then the east portal – he owes his entire career to this commission. But even his companion Brunelleschi did benefit from this competition, as he became well known in Florence and its surroundings.

Without this competition …? Of course, we cannot predict how their lives would have turned out. Probably both gentlemen would have made a career as artists, engineers or architects. But it is doubtful whether it would have been so glorious. For them, the art competition was a once in a lifetime opportunity, an opportunity they seized with both hands and that allowed their talent to manifest itself fully.

And the name ‘Porta del Paradiso’? Michelangelo thought the eastern gates were the most beautiful thing he had ever seen – beautiful enough to adorn the gates of paradise, he would have said. But there is another, much more prosaic explanation. The Gates of Paradise gave out on to a cemetery that lay squeezed between the baptistery and the cathedral. The name of that cemetery was ‘Il Paradiso’ (Paradise), hence the name ‘Gates of Paradise’.

Ghiberti depicted himself on the Gates of Paradise. On the edge of the left gate, you can see all kinds of small, beautifully styled heads. Ghiberti’s head is on the right edge of the left gate, the fourth from above, the man with the shiny bald skull.

2. Dome of Florence Cathedral

Piazza del Duomo

Now turn around and behold one of the wonders of Western architecture, the dome of the Duomo Santa Maria del Fiore, still the largest brick dome in the world today.

View position in Google Maps.

The first stone of the cathedral was laid in 1296 and one hundred years later, at the beginning of the 15th century, the cathedral stood up straight. However, something fundamental was missing from the construction, namely a roof. An ordinary roof span would never have been sufficient for the proud Florentines. It had to be something beautiful and unique, an impressive dome like a sparkling cherry on an equally impressive cake.

The problem was not the design of the dome and determining how wide and high it should be. The building committee had already calculated it in 1368: the dome had to be forty-five metres wide and almost a hundred metres high. The problem was instead technical. How would they mount that gigantic dome on the construction, and do it in such a way that it would last for centuries?

To solve this problem, the Duomo construction committee held another public competition in 1418, and once again Brunelleschi and Ghiberti found themselves facing each other. In the meantime, Brunelleschi had undergone a remarkable transformation. After the lost competition seventeen years earlier for the gates of the baptistery, he had abandoned sculpture to devote himself entirely to architecture, a profession in which he, being trained as a goldsmith, still had everything to learn. Together with his best friend Donatello, he went on a journey to Rome to study ancient buildings. Although it was not allowed, he climbed the Pantheon and discovered that its dome was made up of two layers instead of one. Brunelleschi recorded the secret and applied it years later to the dome of the Florence Cathedral.

In 1420 Brunelleschi began the construction work and in 1436, after having overcome numerous obstacles and seemingly insoluble problems, the cathedral was officially inaugurated. All that was missing were the terracotta roof tiles and the lantern on top of the dome. This was finished in 1452, but without Brunelleschi. The man died in 1446 and was buried under massive public interest in a modest grave in the cathedral, under the dome he had built with his own hands. The inscription on his grave read: ‘CORPUS MAGNI INGENII VIRI PHILIPPI BRUNELLESCHI FIORENTINI’ (Here lies the body of the great ingenious Florentine Filippo Brunelleschi). A fitting tribute to one of the key figures of Renaissance art and Western architecture.

Go investigate yourself. Study the dome, admire that unparalleled blend of monumentality and grace, and pay homage to the architect by visiting his tomb in the crypt of the cathedral. By the way, on the side of the cathedral, to the right of the main entrance, you will find a statue of a seated Brunelleschi looking up at his own dome – or admiring it? The man next to him is Arnolfo di Cambio, the architect and first architect of the cathedral.

3. Ospedale degli innocenti – Foundling Hospital

Piazza della Santissima Annunziata

Go to the back of the cathedral and take Via dei Servi (north-east of the cathedral). Walk down the street until you reach Piazza della Santissima Annunziata. The Ospedale degli Innocenti is on the right.

View route in Google Maps (follows a slightly different road).

This building, an orphanage, is regarded as the first Renaissance building. The name of the orphanage, innocenti or innocents, refers to the slaughter of male children in Bethlehem as ordered by King Herod. It was the first orphanage in Europe to host up to a thousand children at certain times. Some parts are still used as an orphanage today.

The architect was Brunelleschi and his client the Arte della Seta (the guild of silk merchants). Work began in 1419 and was completed in 1426. This means that while Brunelleschi was working on the dome of the cathedral, he also supervised other large projects like this orphanage.

During his ten-year study trip to Rome in the company of Donatello, Brunelleschi was not only after a solution for the dome. He immersed himself in all aspects of ancient architecture and applied several of its principles to his later designs. Brunelleschi did not imitate antique Roman architecture, but blended aspects of classical Roman architecture with the architectural concepts prevailing at the time and originating from the Middle Ages. In so doing, he developed a new style that made him the first Renaissance architect and the founder of a new style that would set the tone in Western architecture until Art Nouveau and later Bauhaus architecture made their entry.

This orphanage is a fine example of this new Renaissance style. The floor plan of the building followed the prevailing medieval model. In Brunelleschi’s time, it was not unusual to surround buildings such as hospitals with arcades. The difference lay in the execution of those arcades. Brunelleschi did not want to create beauty by adding numerous decorations and playful elements, but by turning the arcades into an example of simple and pure harmony. To achieve this, he applied a tight symmetrical plan, which is mainly expressed in the proportions. The slender columns of the arcades, for example, are as high as the arches are wide and the height of the columns is identical to the distance between the architrave and the eaves. Also observe the curvature of the arches – a perfect circle. Simplicity, austerity, mathematical precision, perfect proportions, and symmetry: all characteristics you recognize in his other buildings in Florence and that influenced countless architects after him.

In between the arches, you see ten blue tondos (round paintings or reliefs) with images of orphans and foundlings. Those were made by Andrea della Robbia, an artist who had turned this blue glazed earthenware into his trademark. You’ll find them everywhere in Florence and in other Italian cities and they are almost always made by the studio of Della Robbia. His studio not only worked on prestigious projects for wealthy patricians; it also produced this popular glazed earthenware in large quantities for the common people, a practice that often yielded more money than the expensive but less frequent tailor-made assignments for churches, rich patricians, or a city.

4. Donatello, David (in Bargello)

Via del Proconsolo, 4

Take the small street to the right of the Ospedale degli Innocenti, Via dei Fibbiai. Take the first street on the left, Via degli Alfani, and then take the fourth street on the right, Borgo Pinti. Continue straight ahead, through the Borgo Pinti and the Volta di San Piero, under a covered alley and across Piazza di San Pier Maggiore diagonally to the right into Via Matteo Palmieri. Then turn right into Via Ghibellina. At the end of the street, turn left: the Bargello is at the corner of Via Ghibellina and Via del Proconsolo.

View route in Google Maps.

Seen from the outside, the Bargello looks a bit lugubrious. If Florence were designed as an amusement park, one would undoubtedly refer to Bargello as the haunted house. The grey-brown stones, the small windows covered with bars, the battlements at the top, the proud naked bell tower and the absence of any kind of decoration: this is not a place where you would enter without suspicion. But as it is often the case in Florence, appearances are deceptive. Anyone entering the courtyard is soon enchanted by its elegant harmony and by the most important collection of Renaissance sculptures on earth.

The exterior was not made uninviting without a reason. After all, the Bargello, built in 1255, was originally the headquarters of the podestà, the highest magistrate in the city. The law stipulated that this had to be a foreigner coming from a village or town at least fifty kilometres out of Florence. Moreover, the podestà could stay on for a maximum of one year. That way, the city hoped to appoint an uncontaminated magistrate, someone who knew nothing about the internal power relations and the family feuds, and therefore could judge in an objective way. Later the Bargello was used as a prison. The name of the building refers to the title of the highest magistrate or policeman who occupied it and who was called bargello from the end of the 16th century onwards.

Since 1865 the building houses a museum of Renaissance sculpture. You will find a beautiful collection of sculptures by Michelangelo, Donatello, Ghiberti, Giambologna, Verrocchio and others. The bronze panels made by Ghiberti and Brunelleschi for the baptistery are on display here. Check for yourself if the jury made the right decision by choosing Ghiberti.

One of the most remarkable sculptures from the Bargello collection is the David of Donatello. For various reasons this is a revolutionary sculpture. The statue, for example, is made of bronze, which was particularly expensive at the time and usually reserved for monuments to kings, princes, condottieri, and official urban authorities. Furthermore, with this statue Donatello introduced an important innovation in art because it was the first freestanding nude since antiquity. But it was also new in terms of content and concept. Donatello did not portray the hero David, the defender of republican freedom and revered throughout Florence, as a tough and cunning warrior who defeated the giant Goliath with one well-aimed throw. No, he portrayed him as a sensual hermaphrodite, an ambiguous mixture of boyish and feminine characteristics. We don’t know how people responded to Donatello’s image. It’s true that the Florentines were familiar with ambiguous symbolism, but I find it hard to imagine that this sculpture did not face a great deal of displeasure and resistance.

It’s not sure who did commission the sculpture. Probably it was Cosimo de’ Medici, the leader of the Medici clan. What we do know is that Cosimo eventually installed the work in his home, not hidden in a back garden, but in the cortile of the Palazzo Medici, just behind the main entrance. Everyone who entered the Medici Palace, all dignitaries, local and foreign merchants, priests, bishops, princes, and heads of government, had to pass by. In addition to his open support for this statue, there are other signs that Cosimo repeatedly stuck his neck out for innovative, complex, and provocative art. A feature that seemed to permeate the entire city and in which it differed from its counterpart from the north, the rather protectionist Venice.

So, if you have the time today or tomorrow, don’t be put off by the rough exterior and the dark past of the building and pay a visit to the Bargello.

Back to overview walking tour.

5. Palazzo Vecchio (or Palazzo della Signoria)

Piazza della Signoria

Continue along Via del Proconsolo in a southerly direction (turn right when facing the Bargello) over Piazza di San Firenze and turn right into Via dei Gondi. Continue along until you reach Piazza della Signoria.

View route in Google Maps.

From a wealthy city such as Florence, regarded as the centre of the arts for many centuries, you’d expect it to blow you away with its government building. That it is as magnificent, refined, and spectacular as the artists who produced it and as the cathedral and its dome. But frankly, at first sight it is not. Neither fish nor fowl, would be your first impression. A crossover between a fortress and a town hall. A building that wants to be an impregnable castle but, for all sorts of practical reasons, has only retained its visible features – robust stone, battlements, shields, tower – and has pushed aside its essential features – size, thickness of walls, moat, drawbridge.

One thing you’ll immediately notice is its resemblance to the Bargello. The same basic structure, the same ochre tones, and the same robust appearance. Also, the architects are related. According to Vasari (16th-century art historian and author of Vite), Jacopo di Lapo designed the Bargello and his son Arnolfo di Cambio the Palazzo Vecchio. The latter was also the first architect of the cathedral.

At a second glance, you do notice the difference between the two buildings. The windows of the Palazzo Vecchio are slightly larger than those of the Bargello, the brickwork is more varied, the battlement wider, there are coats of arms underneath the battlement and the tower consists of two parts of which the top seems to sprout from the bottom. Not to mention, in my opinion, the most fantastic feature of this building: the position of the tower. At first, I thought: there’s something wrong. The builders put it there by mistake, while the architect probably wanted to position it in the centre or on the side. But now I have a totally different opinion. I think it’s magnificent. The asymmetrical character of the facade and the tower makes this palazzo one of the most striking and iconic city town halls in the world. And it emphasizes once again the idiosyncratic character of the inhabitants – a trait that was especially manifest in Florence’s political system.

Fifteenth-century Florence was a republic headed by the gonfaloniere di giustizia (standard-bearer of law), assisted by eight priori. All nine had to be members of a guild and together they represented the four Florentine districts. This system was quite complex but not particularly noteworthy. What was remarkable, though, was the time frame within which the priori and the gonfaloniere could rule and the way in which they were chosen. The government changed occupation every two months and the gonfaloniere and the priori were not elected by ballot but by lottery.

Why did the Florentines adopt such a bizarre system? The answer is simple: because they had a deep-rooted aversion to dictatorships. They desperately wanted to avoid one person or one family taking power, so they chose to keep the term of government extremely short and to elect the leaders by lottery.

You might think that such an unstable political system cannot endure. Strangely enough, it did. Florence was an extraordinarily prosperous republic that lasted for four centuries without any major interruption, from the beginning of the 11th century to 1530 – one of the longest-running democracies in our Western history. The great advantage of this system is that it nurtured hopes of social prestige. After all, anyone who was a member of a guild could cherish the justified hope of one day being elected priore or even gonfaloniere in his life and thus gaining the respect of his fellow citizens. In this sense, their political system was the 15th-century version of the American dream. An illusion, because the Florentines never really gained political power, but one that spurred a lot of people into action, kept them alert and dynamized society.

Back to overview Florence City Walk

6. Illustrious Florentines

Uffizi Square

Stand with your back to the Palazzo Vecchio and turn left into Piazzale degli Uffizi.

View route in Google Maps.

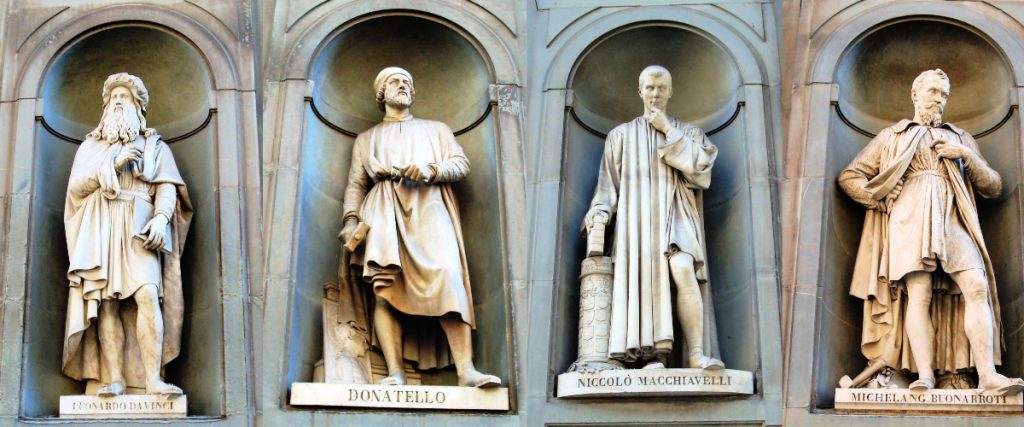

You are now standing in the courtyard of the Uffizi museum, a place that stages many city events. You are not here for the museum but for the twenty-eight images of ‘illustrious’ Tuscany around you. Already in the 16th century Duke Cosimo I had the idea to decorate the niches around this square with heroes of Tuscan history, but the project was only realized in the 19th century, a period of great nationalistic feelings. Each town or village then erected monuments to its local heroes and a Florentine printer, Vincenzo Batelli, felt that his town, which could boast many more and much more impressive celebrities compared to other towns, should not be left behind. At first, he tried to raise funds through an early form of crowdfunding, but when that didn’t work, he successfully set up a large tombola.

The twenty-eight sculptures were made by various sculptors. Among the Tuscan heroes are government leaders, warlords, scientists, writers and artists. The overview is certainly impressive, especially if you know that many 15th-century artists are still missing, such as Brunelleschi, Ghiberti, Fra Angelico, Filippo Lippi, Masaccio, Verrocchio and so on. All figures who have shaped our Western cultural history and over whom there is still much to do today.

7. Santa Croce

Piazza di Santa Croce, 16

Turn right and walk back to Piazza della Signoria. Just before the square and the Palazzo Vecchio, turn right into Via della Ninna. At the end of the street, at the crossroads, turn left into Via dei Leoni and a little further right into the Borgo dei Greci. Continue along this narrow street until you reach Piazza di Santa Croce.

View route in Google Maps.

After Piazza della Signoria, Piazza Santa Croce is Florence’s most important square, meeting place and open-air events hall. This was the place where preachers such as Bernardino of Siena spent hours enthralling the crowd with a mix of heart-warming spiritual messages about human equality, gossip about local life, politically charged statements and many, many juicy anecdotes.

Knight tournaments, jousting, horse races, and games of calcio storico (or calcio fiorentino), an ancient Florentine version of football, were also organised on this square. At the right side of the square, on the ground floor of the building with the many murals (Palazzo dell’ Antella) is a marble circular plaque. This circle commemorates the 10th of February 1565 but serves mainly to mark the line that divides the playing field for calcio storico in two. On the other side is a similar somewhat darker plaque.

The Santa Croce Church on the east side of the square is the second largest church in Florence. Its construction began in 1294 and the master builder was Arnolfo di Cambio, the man who in the same period drew the plans for the cathedral and Palazzo Vecchio and thus shaped the skyline of Florence more than anyone else. In 1442 the church was close to completion. Only the facade had to be clad, a work that was not completed until the 19th century, probably based on an old design.

Santa Croce is the church of the Franciscans, monks who value humility, sobriety, and an ascetic lifestyle, but for the construction of Santa Croce they behaved as ambitious, competitive, and arrogant as their fellow Florentines. They insisted that their church had to become bigger and more imposing than the one of their closest competitors, the Dominican church of Santa Maria Novella in the north-west of the city.

The same paradoxical attitude can be seen in the interior of the church. The Franciscan monks had to beg for their survival, while their church is perhaps the most richly decorated in Florence. Go inside and admire the works of art of great masters such as Giotto and Donatello, have a look at the Pazzi Chapel designed by Brunelleschi, but also look for the tombs and funerary monuments of Florentine celebrities such as Michelangelo, Machiavelli, Leonardo Bruni (one of the first humanists), the scientist Galileo Galilei, the writer Dante Alighieri, the sculptor Lorenzo Ghiberti and the opera composer Gioacchino Rossini.

In the Cappella Bardi, on the left in the transept, there is a wooden crucifix made by Donatello of which his good friend Brunelleschi said that he ‘had placed a peasant on the cross’. According to the story in Vasari’s Vite, a collection of biographies of Italian artists, Donatello reacted angrily to this unexpected criticism and answered him: ‘If you really know it that well, take some wood and make one yourself’. Brunelleschi accepted the challenge and set to work. Wondering what Brunelleschi’s version looks like? Soon we’ll be in Santa Maria Novella. There you can judge for yourself which one of them was the best.

8. The dyers’ district

Corso dei Tintori, 21

When you come out of the Santa Croce church, immediately turn left on to Via Antonio Magliabecchi. Continue straight on up to the Corso dei Tintori. There you turn right. At the intersection with Via dei Benci, turn left and immediately right into Via dei Vagellai. Pass Piazza Mentana and continue along Via dei Saponai until you reach Piazza dei Giudici.

View route in Google Maps.

You won’t find Renaissance architectural gems over here, but pay close attention to the names of the streets: Tintori (dyers), Vagellai (boilers or kettles), Saponai (soapers). All these terms refer to the textile industry, the foundation of the Florentine economy in the 15th century. A quarter to a third of all Florentines worked in this industry. Even for the Medici, known as bankers, textiles formed the basis of their trading empire.

This seems obvious at a time when the textile industry was flourishing in Europe, but for a city like Florence, it was not. The sheep in and around Florence did not produce enough wool to keep their textile industry going and the wool they produced was not of the desired quality. As a result, the Florentines had to import wool, mainly from Great Britain and Portugal. Via the port of Pisa, Livorno, or Venice the wool entered Italy, after which it was transported with donkeys over the graceful but nonetheless sturdy hills to Florence. And as soon as the products were finished, they had to be transported back by donkey carts over the hills and then by ships to the rest of Europe.

So Florence’s location was anything but an advantage for the textile industry, and yet Florentine textiles were sought after all over Europe. The reason? They were of superior quality and were delivered at the right price. The guilds knew that too high a price would weaken their market position and therefore they kept the wages of the workers within limits and forbade any form of workers’ association. But the guilds’ greatest contribution was their strict quality control involving, just before the textile was sold, a final check carried out by the Ufficiali delle macchie (Stain Brigade). Textiles that showed too many defects were immediately destroyed.

The Florentine textile was especially appreciated for its rich, deep colours. Even finished fabrics from Flanders and France were sent to Florence to be dyed. The raw materials for this dyeing (such as alum) were imported from the Mediterranean, the Near and Far East and Africa. This required a complex logistical organisation, because each dye came from a different city or region, sometimes thousands of kilometres away from Florence. By the way, the name of one of the most important Florentine families, the Rucellai, is derived from oricello (orchil), a red-purple dye extracted from lichen and imported from Majorca.

9. Corridoio Vasariano

Lungarno Anna Maria Luisa De’ Medici, 8

Walk as far as the Arno, turn right, and follow the Lungarno Anna Maria Luisa de’ Medici (along the Arno).

View route in Google Maps.

On the Lungarno Anna Maria Luisa de’ Medici, along the banks of the Arno and just past the arcades that lead to the Uffizi museum, you suddenly see a corridor coming out of a wall on your right – as if the structure had been stuck to it. This construction, the Corrido Vasariano, runs along the Arno, turns left at the Ponte Vecchio, and continues across the Arno to Palazzo Pitti.

The one-kilometre-long corridor was built by the 16th-century artist–architect Giorgio Vasari at the request of Cosimo I, ruler of Tuscany since 1537. Cosimo’s goal? To connect his residence, Palazzo Pitti, with his office, Palazzo degli Uffizi. Indeed, the monument that now houses one of the most important art collections in the world was originally an office building (uffizi means offices). By building this corridor, the duke and his relatives isolated themselves further from the population, because now they could walk to the office without entering the streets. This stands in stark contrast to the situation in the first half of the 15th century, when rich and poor lived side by side, met spontaneously in the street and maintained close ties with each other.

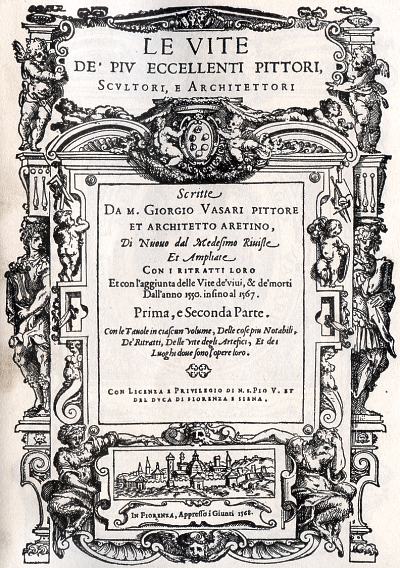

Giorgio Vasari, Self-Portrait (1567)

Cover Giorgio Vasari, Vite

Walk under the arcades that support the Corridoio Vasariano. This is a suitable moment to reflect on its architect, Giorgio Vasari. This former pupil of Michelangelo was himself a deserving, successful and wealthy artist–architect, but in the end, he is best known for his book: Vite de’ più eccellenti architetti, pittori, et scultori italiani, da Cimabue insino a’ tempi nostri (Lives of the most excellent Italian architects, painters and sculptors, from Cimabue to our time), often abbreviated to Vite. Considered to be the very first art history book, this work has spread the idea of Florence as the cradle of the Renaissance like no other. It contains biographies of around 250 artists and is interspersed with treatises on the technical aspects and evolution of art in the 14th and 15th centuries. Vasari divided the art evolution in Renaissance Italy into three phases: in phase one (second half 13th to early 15th century) art was revived thanks to the innovations of Giotto and Cimabue. Phase two (15th century) brought forth artists such as Brunelleschi, Masaccio, Ghiberti, and Donatello and provided further refinement and new techniques such as linear perspective. Phase three (late 15th and 16th centuries) finally brought perfection in painting through figures such as Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael and, the pinnacle of art to Vasari’s mind, his former teacher Michelangelo.

One of the most striking features of Vite is that a disproportionate number of the Italian artists are Florentines, and certainly, according to Vasari, the most important artists Italy had brought forth. Vasari may not have done so deliberately, but his roots and Florentine outlook have ensured that today, in the absence of an equally valid work, we follow his judgment and pay particular attention to Florentine artists and less to those from other cities. A powerful piece of propaganda, therefore, but in a superior form that is attractive both to the general public and to art connoisseurs. By the way, Vasari was not the only great Florentine historian; Florence was full of chroniclers, the most important of which were Leonardo Bruni, Machiavelli and Guicciardini. The fact that they took Florence as the subject of their works has helped to ensure that today we still study this city and its exploits with such great interest.

Back to overview Firenze City Walk .

10. Palazzo Davanzati

Via Porta Rossa, 13 (Piazza dei Davanzati)

Walk along the Arno, on the Lungarno degli Archibusi, to Ponte Vecchio and turn right into Via Por Santa Maria. This street turns left into Via Calimala. At the junction with Via Porta Rossa, on the Mercato del Porcelino, turn left. Continue along this street until you reach Palazzo Davanzati on the left (in Piazza dei Davanzati).

View route in Google Maps.

We are heading to the Palazzo Medici-Riccardi, the house the Medici built in 1444. But let’s first make a short detour to the Palazzo Davanzati to get an idea of the type of house they inhabited before. This palazzo dates back to the 1330s and still has a robust, primitive and medieval look. But when you enter the house, you’ll notice that the Florentine interior designers of that period had more attention for living comfort and aesthetics than the architects of typical medieval castles of that time.

Palazzo Davanzati served as the home and headquarters of a family clan and housed several families. In the centre of the palazzo was a courtyard. It attracted outside light and via a staircase on the outside of the courtyard brought the residents to the rooms on the first, second and third floors. Palazzo Davanzati did not have a rooftop garden like several 15th-century patrician houses, but it did have a loggia on the top floor, added in the 15th century. This enabled the residents to escape the summer heat from time to time. Each room had a fireplace and the walls were richly decorated with lovely scenes full of birds and trees. Note the sturdy wooden shutters. They do not serve as decoration but to shield the glassless window openings from the outside world. Until the 15th century, glass was still rare and reserved for the super-rich.

On the ground floor, you’ll notice three solid doors. They lead to the workshop where the family members and their workmen processed wool, made furniture, or sold fabrics. At the back of the workplace, still on the ground floor, were the rooms of the servants, apprentices and workers. At first glance, this workshop looks rather oppressive, like a basement where you work all day in the dark. But that was not how this space was used back then. The wooden doors were not the end of the workshop but served as the link with the outside world. After all, life in Florence happened outside. Every morning the workers threw open the doors and installed the workbenches in front of the house, so they could work outside and stay in contact with their fellow citizens all day long.

11. Palazzo Medici-Riccardi – Chapel of the Magi

Via Camillo Cavour, 3

Cross the Piazza dei Davanzati and take Via dei Sassetti right in front of you. Walk along Via de’ Vecchietti until you reach Via de’ Cerretani. Turn right. After 150 metres you will see the baptistery on your right. Walk around it on your left and then turn left into Via de’ Martelli. Follow this street all the way to the Palazzo Medici-Riccardi in Via Camillo Cavour.

View route in Google Maps.

This is the home of the notorious Medici clan, the unofficial leaders of Florence from 1434 onwards. The first plan was designed by none other than Filippo Brunelleschi, but Cosimo de’ Medici, the leader of the Medici clan at that time, rejected his plan. Too grand, too ostentatious, too pompous, he felt. He feared that the Florentine people, still in love with their democratic institutions and suspicious of any form of display of power, would take offence. Therefore, he approached one of his confidants, the architect–sculptor Michelozzo (1396–1472) for a more sober and discreet design. The works, started in 1444, were completed around 1460, four years before Cosimo’s death. The strongman of the Medici enjoyed his new home for only a couple of years.

The Palazzo Medici-Riccardi is a great example of early Renaissance architecture. It’s a three-storey block with an open courtyard in the centre, similar to Palazzo Davanzati. Note the horizontal decorative band (girder strip) that delineates the three floors and how the distance between each floor is getting smaller and smaller and the masonry more even – rough at the bottom, slightly more refined in the middle and smooth at the very top. The building is bordered at the top by an overhanging cornice, a feature found in many contemporary Italian palazzi.

Around the palazzo, as in other Florentine palazzi, there is a stone bench attached to the palazzo. This was not added later as a resting place for tourists but was part of the original concept and had a specific purpose. In the second half of the 15th century, many wealthy families such as the Rucellai, the Strozzi, the Pitti … built palazzos like this. They did so in order to live a more comfortable life and to display their wealth, but there was a downside to this trend of building spacious and spectacular palazzos: the rich shut themselves off from the less wealthy. Hence the choice to install a bench around their house. Cosimo de’ Medici regularly sat there to chat with passers-by and keep in touch with the population.

The Palazzo Medici-Riccardi is a beautiful building, one that laid out the contours for later civil architecture. But the real pearl of it is inside: the Cappella dei Magi. The walls of this small house chapel were painted in 1459–1460 by the Florentine fresco painter Benozzo Gozzoli. The beautiful and imaginative fresco painting that covers all the walls of the chapel is a tribute to the Council of Ferrara-Florence of 1439–1443. It tells the story of the three kings on their way to Bethlehem. One of the three is the emperor of the Eastern Roman Empire. A second one is the Patriarch of Constantinople, the religious leader of the East. And the third one is the eleven-year-old Lorenzo de’ Medici (not yet born in 1460), the future leader of the Medici clan. The fresco features many other members of the Medici, including Cosimo de’ Medici himself, the man who led the family at the time of the council.

Merchants and political authorities visiting the Medici obviously received a tour of the chapel. You can imagine what happened: suddenly the visitors are standing face to face with an impressive colourful and life-size painting depicting the Medici accompanied by the most important people on earth. The motif of this apparently innocent and pleasant guided tour? To show other people at what level the Medici operated and to where their tentacles reached. For the Medici the chapel was a propaganda tool to strengthen their might, a status symbol that reflected Cosimo’s social position in society, comparable today to owning a flashy Bugatti, a traditional football club or a villa on the Côte d’Azur with a private beach and luxury yacht.

12. San Lorenzo

Piazza di San Lorenzo

Turn right around the corner from Via Cavour to Via de’ Gori. After a few footsteps you will see the San Lorenzo Basilica looming in front of you.

View route in Google Maps.

The Basilica di San Lorenzo is the centre of the ‘Medici quarter’. This district was dominated by the wealthy banking family and inhabited by Medici supporters. The construction of the church began in 1419, and in 1421 Brunelleschi was appointed architect. Money problems hindered the progress of the works at which point the Medici provided financial assistance and became the actual owners of the church. You can clearly see this from the prominent presence of their emblem (usually six, sometimes five, seven or eight balls on a golden-yellow background) in and around the church, as in the rest of Florence. Look at the pedestal of the statue at the corner of the little square in front of the main entrance. The figure portrayed is Giovanni delle Bande Nere (Ludovico di Giovanni de’ Medici), a Medici-condottiere and father of Duke Cosimo I de’ Medici (1519–1574).

As you can see, the facade is never finished. In the end, the commission was assigned to Michelangelo, but due to all sorts of problems including strikes by the ship’s captains who had to transport the marble to Florence, it was never completed.

San Lorenzo is home to a wealth of cultural–historical treasures, sufficient for a whole day’s exploration. Enter the church and enjoy the bright and harmoniously arranged interior space designed by Brunelleschi, Donatello’s Passion Pulpit and Filippo Lippi’s colourful and graceful Annunciation. The Sagrestia Vecchia (Old Sacristy) was also designed by Brunelleschi and is a fine example of the new Renaissance architecture. The space is clearly divided into two parts. At the bottom of the ornamental border, you see mostly rectangular and above that border circular shapes. All elements and proportions are precisely measured and form a harmonised unity. The reliefs on the life of John the Baptist, the patron saint of the city, are made by Donatello.

Michelangelo also contributed to this complex, including the design of the Sagrestia Nuova (New Sacristy) in the Cappelle Medicee. He was supposed to take care of the frescoes and sculptures so that it would become one of the first integrated works of art, but unfortunately, he was unable to put his ambitious ideas into practice. Other artists have pursued his work, but you can still see some of the master’s sculptures, such as the funerary monument to Lorenzo de’ Medici.

The Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana also emerged from Michelangelo’s multidisciplinary brain and is often regarded as his main architectural achievement. The most spectacular part of the library is the vestibule or reception room and especially the staircase in three parts that leads to the harmoniously furnished reading room. The new library was built to house the rich collection of Medici books, a hobby begun by Cosimo the Elder at the beginning of the 15th century and that resulted in one of the largest collections of books in Europe at that time. Finally, marvel at the mausoleum for the Medici dukes, the lavishly decorated Cappella dei Principi. Vasari drew the plans in the 16th century, but its construction only started in the 17th and was finished in the 19th century.

13. Santa Maria Novella

Piazza di Santa Maria Novella, 18

Take the street at the back of San Lorenzo, Via del Canto dei Nelli, and turn left towards the Arno, past Piazza di Madonna degli Aldobrandini and through Via del Giglio up to Via dei Banchi. Turn right and continue up to Piazza di Santa Maria Novella.

View route in Google Maps.

Santa Maria Novella is the church plus monastery of the Dominican monks, competitors of the Franciscans who founded the Santa Croce church on the other side of town. The construction of this church, begun in 1246, marked the beginning of several architectural interventions that changed the outlook of Florence, such as the cathedral, the Palazzo Vecchio, the Santa Croce Church and the Bargello.

The first thing to take your breath away is the magnificent facade. In 1350, one hundred years after the foundation stone was laid, works on the facade began, but due to a lack of money, they could only finish the lower half. A century later, in 1456, the wealthy merchant Giovanni Rucellai proposed to pay for the other half. He commissioned the architect–writer and uomo universale Leon Battista Alberti who turned it into one of the most beautiful church facades on earth. Different features of the facade point to the Rucellai. First, the inscription underneath the cornice. It reads: ‘IOHANES ORICELLARIUS PAV.F.AN.SAL.MCCCCLXX’ (Giovanni Rucellai, son of Paolo, the blessed year 1470). Just below the moulding separating the top and bottom, you see a pattern of billowing sails, a reference to the coat of arms of the Rucellai that is located at the two extreme sides of the moulding: a lion on top of the waves.

There is plenty to see inside the church, such as the Cappella di Filippo Strozzi with frescoes by Filippino Lippi, the Cappella Maggiore with frescoes by Domenico Ghirlandaio, the frescoes by Paolo Uccello in the Chiostro Verde (the monastery garden) and last but not least, Brunelleschi’s wooden crucifix in the Cappella Gondi, the one he made in response to Donatello’s crucifix in Santa Croce.

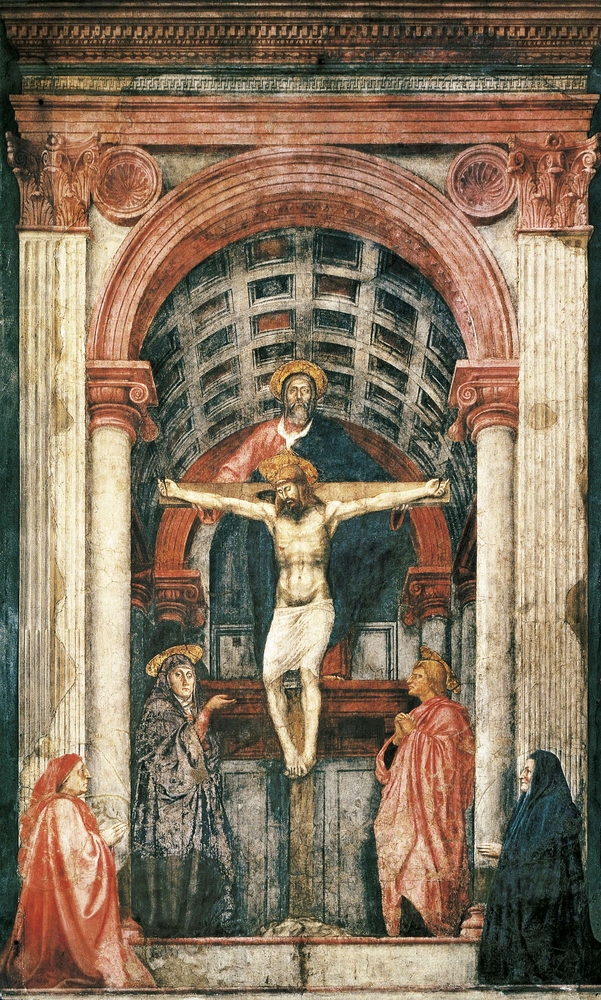

Pay close attention to the Trinità (Holy Trinity) of Masaccio, painted between 1425 and 1428. The young artist did something no one had ever done before: he applied the mathematical laws of perspective to create an illusion of depth, a method he most probably learnt from his friend Brunelleschi.

Basically, it’s just a technical trick: fix a point on the horizon and let all imaginary parallel toplines and underlines of houses, fences, trees, converge in that vanishing point. The consequences of this seemingly simple technical trick were great. A new world of artistic possibilities opened up, not only technical possibilities, but also in composition and choice of subject. Suddenly artists were given the means to depict landscapes and buildings in a natural way, and to construct large-scale spatial scenes with many people and buildings.

This fresco clearly shows how this new technical skill prompted Masaccio to question various aspects of his art and make daring choices. For instance, for his setting he chose a stately, classical-looking chapel with columns, and, as characters, sober massive and angular figures, like sculptures, all to emphasize a sense of depth and volume. The introduction of the mathematical perspective led to numerous innovations in various fields – a herald of the experiments of the great 15th-century Florentine artists after Masaccio such as Da Vinci, Michelangelo and Raphael and how they would further explore the new possibilities of depth, space and volume.

14. Ognissanti

Borgo Ognissanti, 42

Leave Santa Maria Novella behind you, cross Piazza Santa Maria Novella and take the street to the left of the arcades, Piazza degli Ottaviani. This turns into Via dei Fossi. Follow the street to the end, then turn right into the Borgo Ognissanti. Two hundred metres further on your right is the Chiesa di San Salvatore in Ognissanti.

View route in Google Maps.

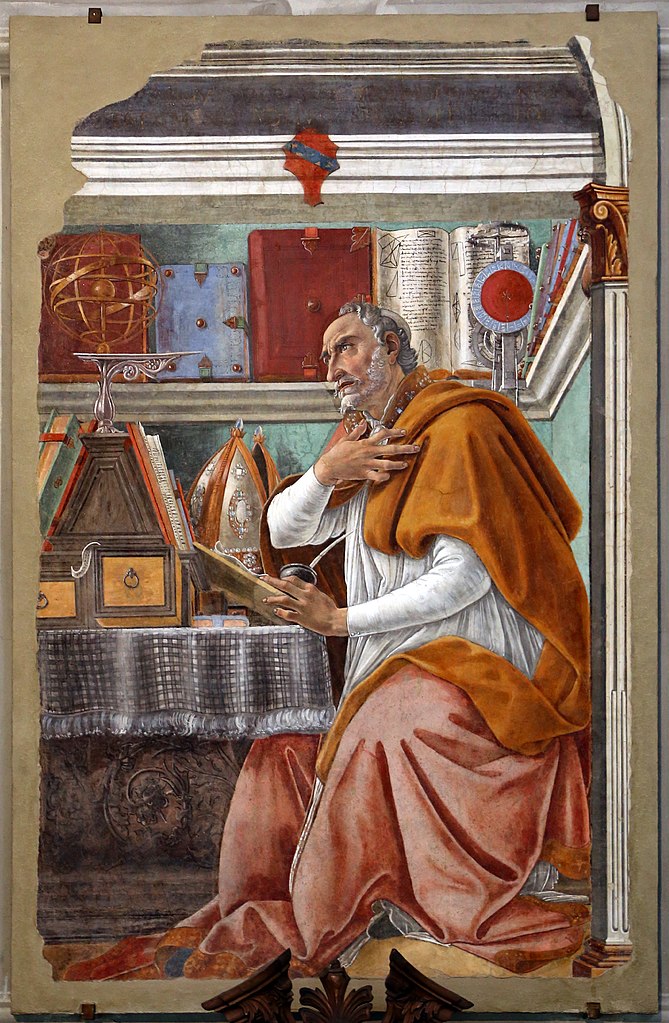

The Ognissanti Church (All Saints Church) doesn’t look like a typical Renaissance church. It dates back to the 1250s and was completely rebuilt in the 17th century in the Baroque style. The Vespucci family, whose most famous descendant was the explorer Amerigo Vespucci, lived in this area, mainly inhabited by wool workers. The Vespucci maintained close contacts with the Filipepi, a family of tanners and leatherworkers who also lived in the neighbourhood and who also produced a great celebrity: the Renaissance painter Alessandro di Mariano Filipepi, better known as Sandro Botticelli (1445–1510) (his nickname ‘Botticelli’ – barrel or keg – probably refers to his older and somewhat thicker brother Giovanni). Botticelli was often hired by the Vespucci, as for the famous Saint Augustine fresco (1480), right in the middle of the church. The coat of arms at the top of the painting belongs to the Vespucci.

Domenico Ghirlandaio, Saint Jerome

Botticelli, Saint Augustine

Photo Botticelli, Saint Augustine by Sailko, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sandro_botticelli,_sant%27agostino_nello_studio,_1480_circa,_dall%27ex-coro_dei_frati_umiliati,_01.jpg, license: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/deed.en.

Directly opposite is a similar fresco by Domenico Ghirlandaio, The Saint Jerome (1480). Both frescoes are depictions of saints in their study room and both are influenced by the Flemish primitives and more specifically by Saint Jerome in His Study Room by Jan Van Eyck, which, it is said, was then owned by Lorenzo de’ Medici. Look at the differences between the two versions. Saint Jerome looks at the viewer in a relaxed way, while Augustine seems to be seized by divine inspiration and is trying to connect with the heavenly.

Ghirlandaio painted several frescoes in this church, including one in the chapel in front of the Vespucci. In the fresco Maria of Mercy and Lamentation, under Maria’s cloak are several members of the Vespucci family including, some say, the young Amerigo Vespucci, to the right of Maria. It is also rumoured that the young uncovered woman with the red cloak on the other side is Simonetta Vespucci. Some claim that she modelled for Botticelli’s world-famous Birth of Venus – a claim rejected by many art historians as pure nonsense since she died about ten years before Botticelli painted his masterpiece.

Botticelli is buried in this church, in one of the chapels in the right aisle. On his deathbed he said he wanted to be buried at Simonetta’s feet, feeding suspicions that the relationship between the two was more than pure business. The exact location of Simonetta’s tomb in this church is not known. This woman, widely acclaimed as the most beautiful woman in the city and to be seen in numerous Florentine paintings, died in 1476 at the age of twenty-two, probably as a result of tuberculosis.

Check out the refectory of the church. There is a beautifully subdued fresco, The Last Supper by Ghirlandaio. Once again you witness how the Florentine artists experimented with all kinds of perspective techniques to create an illusion of depth. By incorporating the architecture of the refectory into the fresco, for instance, the viewer has the impression that the scene is taking place here and now and that he or she is part of it. Leonardo da Vinci was a great admirer of Ghirlandaio’s Last Supper and he undoubtedly was inspired by it for his own world-famous Last Supper at the Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan.

Going out of the church you’ll notice the Palazzo Lenzi on your right, one of the most beautiful Renaissance palazzi in Florence. It was built in 1470 and is sometimes called the ‘palazzo degli enigmi’ because historians have long been speculating about its architect. Was it Brunelleschi, as Vasari claimed, Michelozzo, or a hitherto unknown Florentine architect still waiting to be discovered?

15. Ponte Amerigo Vespucci

Ponte Amerigo Vespucci

Cross the Piazza Ognissanti as far as the Arno and turn right into the Lungarno Amerigo Vespucci. Follow the Arno up to Ponte Amerigo Vespucci and cross the bridge.

View route in Google Maps.

Admittedly, the Ponte Amerigo Vespucci is not the most charming bridge over the Arno, but it is a nice place to take a break and have a glimpse of the city’s skyline. You can see the tower of Palazzo Vecchio and if you look closely you can catch a glimpse of the dome.

Florence is not a city of sailors. That’s hardly surprising. The city is not located by the sea and did not have an extensive sea fleet like that of Genoa or Venice. And yet the Florentines played a significant role in the great voyages of discovery of the 15th and 16th centuries. One of its inhabitants, Paolo dal Pozzo Toscanelli, inspired Columbus to sail westwards across the Atlantic Ocean to India, a journey that enabled him to discover America. Another one, Giovanni da Verrazzano, explored the east coast of North America and was the first Westerner to visit the bay of New York. And the name of a third Florentine, the explorer Amerigo Vespucci, is likely to last longer than that of any Florentine artist, including Da Vinci and Michelangelo, because fortune granted him the honour of naming two continents – South and North America – after him, the only continents on earth that bear the name of a mortal human being. The appreciation of someone’s accomplishments could not be greater, but it should be mentioned that this immense honour is not in proportion to Amerigo’s merits because it was not he but Columbus who first set foot in America.

Amerigo’s ancestors, the Vespucci, were a family of poor immigrants from Peretola, a village near Florence. The first Vespucci to arrive in Florence were wine merchants, not a highly valued profession at the time. But Simone Vespucci, Amerigo’s ancestor, embarked on a different career path. He opted for a career as a silk manufacturer, worked his way up and amassed great wealth. Simone’s descendants worked diligently in his footsteps and joined the right political family, the Medici. As a result, the Vespucci settled regularly in the Signoria from 1443 onwards and in 1447 one of them was even chosen as gonfaloniere, an achievement that brought the immigrants to the top of the Florentine social ladder.

Their good luck, however, did not last for too long. A couple of years later Amerigo Vespucci’s father had fallen back to the modest level of notary. But thanks to the family’s good historical ties with the Medici, Amerigo got the chance to work for them. During his business trips for the Medici he met some sailors, decided to make his own career as an explorer and travelled to America. Initially, he thought that the areas Columbus had reached were Asia, but during one of his next voyages he became convinced that it was a ‘mundus novus’. He described his experiences of this new world in letters that were published and widespread thanks to the wonders of the recently developed printing press, with the unexpected result that a German cartographer, Martin Waldseemüller, decided to name the newly discovered continent after him, Amerigo Vespucci, a descendant of poor Florentine immigrants. Four hundred years after his death, the Florentines felt that their hero had not yet been given enough honour and named this modern bridge after him.

16. Brancacci Chapel (Santa Maria del Carmine)

Piazza del Carmine, 14

Continue along the Ponte Amerigo Vespucci, through the Via Sant’Onofri to the Borgo San Frediano. Turn left there and walk 250 metres further to turn right over Piazza del Carmine until you reach Santa Maria del Carmine.

View route in Google Maps.

In this part of town, Oltrarno (across the Arno), you see far fewer tourists. It’s much calmer over there than in the city centre. Feel free to spend a whole day exploring this area but be sure to visit the Brancacci Chapel in the Carmelite church Santa Maria del Carmine. According to many, including myself, you’ll find there the most beautiful frescoes of Florence, a colourful and profound pearl hidden in the side chapel of one of the least spectacular church facades in Italy. But don’t be fooled by the somewhat dreary and unfinished exterior. Enter the door to the right of the main entrance and let yourself be taken in by what is sometimes called the Sistine Chapel of the Early Renaissance.

Three Florentine artists have worked on this fresco cycle: Masaccio, Masolino and Filippino Lippi. The first two laid the foundations but left the frescoes unfinished around 1427–1428, after which Filippino Lippi finished them in 1484–1485. The art-historical importance of these frescoes lies mainly in the innovations introduced by Masaccio, which are emphasised by the difference in approach between him and his eighteen-year older collaborator Masolino. Compare, for example, Masaccio’s Expulsion from Paradise with the opposite fresco, Masolino’s The Fall.

Masolino, The Temptation of Adam and Eve

Masaccio, The Expulsion from the Garden of Eden

Masolino, a proponent of the then prevailing international style or International Gothic, painted elegant serene figures who seem to have run away from a harmonious and courtly fantasy world. Masaccio’s universe, on the other hand, was full of human drama and spatial depth. He was one of the first to use light and dark surfaces to add body and consistency to the figures depicted, an approach that differed greatly from Masolino’s flat lines. Masaccio also used linear perspective and natural light to enhance the illusion of space and reality. And to create even more depth in the landscapes, he gradually illuminated the colour tones of the mountains beyond. Facial expression, lighting, linear perspective, colour tones: Masaccio experimented with a wide range of techniques to enhance the sense of realism of the scenes and create an illusion of space.

Typical of this new style is the most famous scene in the fresco cycle, Pagamento del tributo (The Tribute Money), a scene in which Jesus discusses the righteousness of taxes with his apostles and bystanders. The figures of Jesus and the apostles are, despite the halo above their heads, not light-footed frolicking angels, but human beings made out of flesh and blood and with their feet firmly on the ground – fishermen and merchants who, moreover, are situated in a landscape that is unmistakably Tuscan. What reinforces the realism is the fact that this scene was painted around 1427, at a time when a new much-discussed tax law, the catasto, was introduced in Florence. It was as if Masaccio wanted to translate a Bible scene into the Florentine reality of that time.

Masaccio is not very well known, but his influence on Western painting is considerable. All of the great Florentine artists who came after him, Fra Angelico, Filippo Lippi, Piero della Francesca, Da Vinci, Michelangelo and Raphael have studied Masaccio’s frescoes thoroughly and have been profoundly influenced by this precocious genius who unfortunately and in dark circumstances died at the age of twenty-seven.

Masaccio depicted himself in one of the frescoes, in Raising of the Son of Theophilus and St Peter Enthroned, just under the Tribute Money. Masaccio and Filippino Lippi both worked on this fresco. At the far right in front of an open door are four men. The one looking at the audience is Masaccio. The man behind him is Brunelleschi, to his left is Leon Battista Alberti and the little man to his right, barely visible, is Masolino. The depiction of contemporaries and of the painter himself (who usually looks at the public) is another innovation of Masaccio’s that was enthusiastically adopted by other painters.

And now? Let’s go for an aperitivo in Piazza Santo Spirito, far from the tourist crowds. When leaving the Santa Maria del Carmine, turn right into Via Santa Monaca. At the end of the street, turn right into Via Santa’Agostino. A little further on your left you’ll find a large square with the Basilica di Santo Spirito on the other side. Enjoy.

View in Google Maps.

About De geniale stad (The City of Genius)

The 15th century was a golden age for Florence. An exceptional heyday that produced a large number of geniuses such as Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Raphael, Machiavelli, Botticelli, Brunelleschi, Donatello, Fra Angelico, Lorenzo de’ Medici, Amerigo Vespucci, and many others.

These artists and scholars launched the Renaissance, developed fundamental innovations in art and created masterpieces that are admired all over the world and have had a great influence on Western culture. Where did this unparalleled explosion of talent come from and how can it be explained? How is it possible that a town with barely sixty thousand inhabitants produced so many geniuses in only a hundred years?

Based on nine genius-enhancing conditions and illustrated by stories about the genesis of the many masterpieces, Koen De Vos sketches a picture of the creative dynamics in 15th-century Florence. You will discover what made the city so special and how the Florentine artists and thinkers determined the course of (art) history forever.

More information about the book can be found here:

English: https://www.koendevos.com/book-florence-the-city-of-genius.

Dutch: https://www.koendevos.com/florence-de-geniale-stad/

About Koen De Vos

Koen De Vos studied Romanesque philology in Ghent and Rome with a focus on Italian language and literature, Italian culture in Bologna and Italian Renaissance art at Oxford. He is the author of De geniale stad: Waarom Florence zoveel geniën voortbracht in haar houden 15de eeuw (The City of Genius: Why Florence produced so many geniuses in its golden 15th century), published in 2019 by AMBO ANTHOS.